From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The bluefin trevally, Caranx melampygus (also known as the bluefin jack, bluefin kingfish, bluefinned crevalle, blue ulua, omilu and spotted trevally), is a species of large, widely distributed marine fish classified in the jack family, Carangidae. The bluefin trevally is distributed throughout the tropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, ranging from Eastern Africa in the west to Central America in the east, including Japan in the north and Australia in the south. The species grows to a maximum known length of 117 cm and a weight of 43.5 kg, however is rare above 80 cm. Bluefin trevally are easily recognised by their electric blue fins, tapered snout and numerous blue and black spots on their sides. Juveniles lack these obvious colours, and must be identified by more detailed anatomical features such as fin ray and scute counts. The bluefin trevally inhabits both inshore environments such as bays, lagoons and shallow reefs, as well as deeper offshore reefs, atolls and bomboras. Juveniles prefer shallower, protected waters, even entering estuaries for short periods in some locations.

The bluefin trevally is a strong predatory fish, with a diet dominated by fish and supplemented by cephalopods and crustaceans as an adult. Juveniles consume a higher amount of small crustaceans, but transfer to a more fish based diet as they grow. The species displays a wide array of hunting techniques ranging from aggressive midwater attacks, reef ambushes and foraging interactions with other larger species, snapping up any prey items missed by the larger animal. The bluefin trevally reproduces at different periods throughout its range, and reaches sexual maturity at 30–40 cm in length and around 2 years of age. It is a multiple spawner, capable of reproducing up to 8 times per year, releasing up to 6 million eggs per year in captivity. Growth is well studied, with the fish reaching 194 mm in its first year, 340 mm in the second and 456 mm in the third year. The bluefin trevally is a popular target for both commercial and recreational fishermen. Commercial fisheries record up to 50 tonnes of the species taken per year in the west Indian Ocean, and around 700 lbs per year in Hawaii. The rapid decimation of the Hawaiian population due to overfishing has led to increased research in the aquaculture potential of the species, with spawning achieved in captivity. Despite its popularity as a table fish, many cases of ciguatera poisoning have been reported from the species.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The bluefin trevally is classified within the genus Caranx, one of a number of groups known as the jacks or trevallies. Caranx itself is part of the larger jack and horse mackerel family Carangidae, a group of percoid fishes in the order Perciformes.[1]

The species was first scientifically described by the famed French naturalist Georges Cuvier in 1833 based on specimens collected off Waigio, Indonesia; one of which was designated to be the holotype.[2] He named the species Caranx melampygus, placing the species in the jack genus Caranx which had been established by Bernard Lacépède three decades previously. The name’s specific epithet is derived from the Latin translation of “black spotted”.[3] This is still currently considered the correct placement, however later authors placed in other now defunct genera (Carangus and Carangichthys) which has since been deemed incorrect, and the original classification stands.[4] The species was independently redescribed and named seven times after Cuvier’s initial description, with all of these names assigned between 1836 and 1895. The names C. bixanthopterus and C. stellatus were often used in the literature, and were variably classed as synonyms of C. melampygus or valid individual species after their naming. This confusion culminated in Yojiro Wakiya concluding in 1924 they should be treated as separate species.[5] The taxonomy of the species was finally revised by Frederick Berry in 1965, who resolved these two names as being synonymous with C. melampygus, and placed several other names in synonymy with C. melampygus.[5] Under ICZN nomenclature rules, these later names are deemed junior synonyms of C. melampygus and rendered invalid.[4] The species has not been included in any detailed phylogenetic studies of the Carangidae.

The species is most commonly referred to as the ‘bluefin trevally’, with the species’s distinctive blue fins contributing to most of its other common names. These include bluefin jack, bluefin kingfish, blue ulua, omilu, bluefinned crevalle and spotted trevally. The species has many other non-English names due to its wide distribution.[6]

Description

The bluefin trevally is a large fish, growing to a maximum known length of 117 cm and a weight of 43.5 kg,[6] however it is rare at lengths greater than 80 cm.[7] It is similar in shape to a number of other large jacks and trevallies, having an oblong, compressed body with the dorsal profile slightly more convex than the ventral profile, particularly anteriorly. This slight convexity leads to the species having a much more pointed snout than most other members of Caranx.[8] The dorsal fin is in two parts, the first consisting of 8 spines and the second of 1 spine followed by 21 to 24 soft rays. The anal fin consists of 2 anteriorly detached spines followed by 1 spine and 17 to 20 soft rays.[9] The pelvic fins contain 1 spine and 20 soft rays.[10] The caudal fin is strongly forked, and the pectoral fins are falcate, being longer than the length of the head. The lateral line has a pronounced and moderately long anterior arch, with the curved section intersecting the straight section below the lobe of the second dorsal fin. The curved section of the lateral line contains 55-70 scales[10] while the straight section contains 0 to 10 scales followed by 27 to 42 strong scutes. The chest is completely covered in scales.[11] The upper jaw contains a series of strong outer canines with an inner band of smaller teeth, while the lower jaw contains a single row of widely spaced conical teeth. The species has 25 to 29 gill rakers in total and there are 24 vertebrae present.[7] The eye is covered by a moderately weakly developed adipose eyelid, and the posterior extremity of the jaw is vertically under or just past the anterior margin of the eye.[7] Despite their wide range, the only geographical variation in the species is the depth of the body in smaller specimens.[5]

The upper body of the bluefin trevally is a silver-brassy colour, fading to silvery white on the underside of the fish, often with blue hues. After they reach lengths greater than 16 cm, blue-black spots appear on the upper flanks of the fish, with these becoming more prolific with age.[9] There is no dark spot on the operculum. The species takes its name from the colour of its dorsal, anal and caudal fins, which are a diagnostic electric blue. The pelvic and pectoral fins are white, with the pectoral fin having a yellow tinge. Juvenile fish do not have the bright blue fins, instead have dark fins with the exception of a yellow pectoral fin.[8] Some juvenile fish have also been recorded as having up to five dark vertical bars on their sides.[5]

Distribution

The bluefin trevally is widely distributed, occupying the tropical and subtropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, ranging along the coasts of four continents and hundreds of smaller islands and archipelagos.[7] In the Indian Ocean, the species easternmost range is the coast of continental Africa, being distributed from the southern tip of South Africa[12] north along the east African coastline to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. The species’ range extends eastwards along the Asian coastline including Pakistan, India and into South East Asia, the Indonesian Archipelago and northern Australia.[6] The southernmost record from the west coast of Australia comes from Exmouth Gulf.[13] Elsewhere in the Indian Ocean, the species has been recorded from hundreds of small island groups including the Maldives, Seychelles, Madagascar and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.[6]

The bluefin trevally is abundant in the central Indo-Pacific region, found throughout all the archipelagos and offshore islands including Indonesia, Philippines and Solomon Islands. Along continental Asia, the species has been recorded from Malaysia to Vietnam and mainland China.[6] Its offshore range does extend north to Hong Kong, Taiwan and southern Japan in the north western Pacific.[7][10] In the south, the species reaches as far south as Sydney in Australia.[13] Its distribution continues throughout the western Pacific including Tonga, Western Samoa and Polynesia, and the Hawaiian Islands.[11][14] The easternmost limit of the species distribution is the Mesoamerican coastline between Mexico and Ecuador in the central eastern Pacific,[7] including islands such as the Galápagos Islands.[15]

Habitat

The bluefin trevally occurs in a wide range of inshore and offshore marine settings throughout its range, including estuarine waters. The species is known to move throughout the water column; however is most often observed in a demersal setting, swimming not far from the seabed.[16] In the inshore environment, the species is present in almost all settings including bays, harbours, coral and rocky reefs, lagoons, sand flats and seagrass meadows.[17][18][19] Juveniles and subadults are more common in these settings, and prefer these more protected environments, where they live in water to a minimum of around 2 m depth.[20] Adults tend to prefer more exposed, deeper settings such as outer reef slopes, outlying atolls and bomboras, often near drop offs,[15] with the species reported from depths up to 183 m.[20] Adults often enter shallower channels, reefs and lagoons to feed at certain periods during the day.[17] The bluefin trevally displays some habitat partitioning with giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis, tending to be more common outside the major bays than their relatives.[21]

Juvenile and subadult bluefin trevally have been recorded in estuaries in several locations,[18] and generally occupy large, open estuaries up to the middle reaches of the system. These estuaries are often lined by mudflats and mangroves, however the species rarely enters these shallow waters.[22] Individuals of between 40 and 170 mm have been recorded in South African estuaries, where they are the least tolerant carangid to the brackish and freshwater conditions of these systems. Bluefin trevally can tolerate salinities of between 6.0 and 35 ‰, and only occupy clear, low turbidity waters. There is evidence the species is only resident in these estuaries for short periods.[23] The species is also absent from coastal lakes that many other carangids are known from.[22]

Biology and ecology

The bluefin trevally is a schooling species as a juvenile, transitioning to a more solitary fish with well defined home ranges as an adult.[24] Adults do school to form spawning aggregations or temporarily while hunting, with evidence from laboratory studies indicates bluefin trevally are able to coordinate these aggregations over coral reefs based on the release of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) from the reef. DMSP is a naturally occurring chemical produced by marine algae and to a lesser extent corals and their symbiotic zooxanthellae.[25] The number of fish present in an area is also influenced by tidal factors and possibly the abundance of prey and other environmental factors.[24] Tracking studies in Hawaii have found bluefin trevally patrol back and forth along a home range of patch reef walls during the day, only stopping for variable periods where major depth changes or discontinuities in the reef were present. Several fish patrol the same reef patch, reversing direction where the others do. While most fish patrol the one reef, some have been observed to make excursions to nearby reefs, before returning to their home reef later.[26] Night time movements are less extensive than daytime movements, with the trevally moving rapidly between several small reef sections, before slowing down and milling in one patch for around an hour. The fish living in a particular region congregate in one area at night, before returning to their individual daytime range during the day. The reason for this congregation is unclear, but may be important to the social structure of the species.[26] Long term studies have found the fish may range up to 10.2 km over several months, however, is much less restricted in its movements than its relative, the giant trevally.[27] A Hawaiian biomass study found the species to be one of the most abundant large predators in the islands, however it is less abundant in the heavily exploited Main Hawaiian Islands compared to the remote Northwest Hawaiian Islands. The main difference in these populations was the relative lack of large adult fish in the inhabited areas compared to the remote, unfished regions.[28] A study on carangids caught during a fishing tournament in Hawaii found the bluefin trevally is the most common trevally species taken, accounting for over 80% of the carangid catch. The authors note that this may not only reflect its abundance, but also it vulnerability to specific fishing methods used in the tournament.[21] Apart from the typical predator-prey relationship the species shows (described later), an individual of the species has been seen to rub itself against the skin of a Galapagos shark, apparently to rid itself of parasites. This behaviour is also observed in rainbow runner and is a rare example of a commensal cleaner relationship where the cleaner does not gain anything.[29]

Diet and feeding

The bluefin trevally is a fast swimming, mainly piscivorous predator[30] which shows a wide range in hunting techniques.[31] Two studies of adult fish in Hawaii found fish to be the dominant food type in the species, making up over 95% volume of the stomach contents by weight.[21] Here the main fish selected were small reef dwellers, with fish from the families Labridae, Mullidae, Scaridae and Priacanthidae being the most common. Despite the preference of several families, bluefin trevally do take a very wide variety of fish in small amounts, including various species of eel.[16][21] The species appears to have a preference for fish of a specific size, which depends on its own length and age.[32] Cephalopods (mainly octopus or squid)[21] and a wide array of crustaceans are also taken in smaller quantities, with shrimps, stomatopods and crabs being the most common.[12][16] The diet of juveniles in Hawaiian and South African estuaries has also been determined, with these younger fish having a more crustacean based diet than the adults.[18][23] In Hawaii, crustaceans make up 96% of the gut contents numerically, with tanaids and isopods dominating the diet, while fish (mainly gobioids) only make up 4% numerically.[18] Juveniles less than 170 mm in South African estuaries feed predominantly on mysids and paenid prawns, before shifting to a more fish based diet at larger sizes. Small fish are able to effectively filter these small crustaceans from the water, while adults are not.[23] In both cases, a transition to a more fish based diet with age was found to occur, although the length at which this transition occurred varied between location.[18] The diet overlap with the similar C. ignobilis is low in the Hawaiian Islands, suggesting there is some separation of feeding niches.[16] Calculations suggest each individual bluefin trevally consumes around 45 kg of fish per year on average, making it one of the most effective predators in this habitat.[16]

The bluefin trevally displays a remarkable array of hunting techniques, ranging from midwater attacks to ambush and taking advantage of larger forage fish. The species is reported to hunt during the day, particularly at dawn and dusk in most locations;[30] however it is known to be a nocturnal feeder in South Africa.[12] The bluefin trevally hunts both as a solitary individual and in groups of up to 20, with most fish preferring an individual approach.[24] In groups, these fish will rush their prey, and disperse the school, allowing for isolated individuals to be picked out and eaten,[24] much in the way the related species, giant trevally have been observed to do in captivity.[33] In some cases, only one individual in a group will attack the prey school. Where the prey is schooling reef fishes, once the prey school has been attacked, the trevally chases down the prey as they scatter back to cover in the corals, often colliding with coral as they attempt to snatch a fish.[31] While hunting in midwater, fish swim both against and with the tide, although significantly more fish hunt when swimming with the tide (i.e. ‘downstream’), suggesting some mechanical advantage is gained when hunting in this mode.[24] Another method of attack is ambush; in this mode the trevally change their colour to a dark pigmentation state and hide behind large coral lumps close to where the aggregations (often spawning reef fish) occur.[31] Once the prey is close enough to the hiding spot, the fish ram the base of the school, before chasing down individual fish. These dark fish in ambush mode vigorously drive away any other bluefin trevally that stray too close to the aggregation.[31] Ambushes have also been observed on small midwater planktivorous fishes are moving to or from the shelter of the reef.[24] In many cases, the species uses changes in the depth of the reef such as ledges to conceal its ambush attacks. Bluefin trevally also enter lagoons as the tide rises to hunt small baitfish in the shallow confines, leaving as the tide falls.[34] The species is also known to follow large rays, sharks and other foraging fish such as goatfish and wrasse around sandy substrates, waiting to pounce on any disturbed crustaceans or fish which are flushed out by the larger fish.[30][35]

Life history

The bluefin trevally reaches sexual maturity at between 30 and 40 cm in length and around 2 years in age,[36] with one study Hawaii suggesting maturation occurs at a length of around 35 cm on average.[16] There is also a difference in the length at maturation between the two sexes, with females on average reaching maturity at 32.5 cm length, while males attain maturity at 35 cm on average.[16] Sex ratios in the species vary by location with population off east Africa being skewed towards males (M:F = 1.68:1),[36] while in Hawaii the opposite is true with the M:F ratio being 1:1.48.[16] The period of the year over which spawning occurs is also variable by location, with African fish reproducing between September and March[36] while in Hawaii this occurs between April and November, with a peak in May to July.[16] Natural spawning behaviour in the species has never been observed,[37] although large aggregations of bluefin trevally observed in Palau consisting of over 1000 fish are believed to be for the purpose of spawning.[17] Extensive studies on the species in captivity has revealed the species to be a multiple spawner, capable of spawning at least 8 times a year, and up to twice in 5 days.[38] Spawning events are often clustered in a few consecutive or alternate days, usually in the third or fourth lunar phases. Spawning apparently occurs at night to minimise predation on eggs.[38] Fecundity in the natural environment has been reported to range from around 50 000 to 4 270 000, with larger individuals releasing more eggs.[16] Studies in captive fish show females may produce over 6 000 000 eggs per year. These eggs are pelagic and spherical, with diameters between 0.72 and 0.79 mm.[38]

The development of the bluefin trevally larvae after hatching has been briefly described in a study of changes in the digestive enzymes of the species. The species has depleted its storage of energy from the egg at 3 days old, with a series of transformations including coiling of the gut and fin formation occurring before flexion at 26 days of age.[39] Digestive enzymes active from hatching to 30 days old show an apparent shift from carbohydrate utilisation to protein and lipid utilisation as the larvae grows older.[39] Measurements from juveniles in Hawaii indicate the fish is around 70 mm by 100 days and 130 mm by 200 days.[18] Otolith data fitted to the von Bertalanffy growth curve shows the species grows to 194 mm in its first year, 340 mm in the second and 456 mm in the third year. It reaches 75 cm by 8 years of age and 85 cm by 12 years.[16] This model also suggests a growth of 0.45 mm/day; while laboratory feeding studies found the fish grow at an average of 0.4 mm/day in these confined conditions.[16] The maximum theoretical size indicated from the growth curves is 89.7 cm,[16] much less than the 117 cm reported as the known maximum size.[6] Juveniles often enter estuaries, however the species is not estuary dependant as breeding is known to occur where no estuaries are present, suggesting the use of these habitats is facultative. The fish move from these shallower inshore waters to deeper reefs as they grow.[18]

Two hybridisation events in the species are known from Hawaii; the first with the giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis and the second with the bigeye trevally, Caranx sexfasciatus. Both were initially identified as hybrids by intermediate physical characteristics, and were later confirmed by DNA sequencing.[37] It has been suggested these hybrids resulted from mixed species schooling during spawning periods. It is thought that hybridisation is more likely if one or both parent species is rare in an area, which is the case in much of the Main Hawaiian Islands, where overfishing has severely depleted all trevally species populations.[37]

Relationship to humans

The bluefin trevally is an important species to both commercial fisheries and anglers, with the popularity of the fish leading to extensive aquaculture trials. The catch statistics for the bluefin trevally are poorly reported in most of its range, with only parts of the western Indian Ocean supplying information to the FAO. In this region, catch levels have fluctuated between 2 and 50 tonnes in the past decade.[40] Hawaii also keeps catch records, with these showing the species is taken in far less numbers than the giant trevally, with only 704 pounds taken compared to 10 149 lbs of giant trevally in 1998.[41] In Hawaii, the nearshore stocks of the species have been in decline since the early 1900s, with commercial landings dropping over 300% from 1990 to 1991, and have not recovered.[38] Most bluefin trevally sold in Hawaii are now imported from other Indo-Pacific nations.[38] The species is taken by a variety of netting and trapping methods, as well and by hook and line in commercial fisheries. It is usually sold fresh, as well as frozen or salted.[8] The rapid decline in the population has seen a focus on breeding the bluefin trevally in captivity. The species’ aquaculture potential was first investigated in a 1975 experiment in French Polynesia, where juveniles of the species were caught in the wild and transported back to a laboratory. The study found the fish grew to a commercial size of 300 g in 6 to 8 months and only suffered a 5% mortality rate. It was concluded that such a technique carried out on a larger scale in lagoons would be promising due to the growth rate and relatively high price commanded by the species at market.[42] Further investigations into the potential for offshore aquaculture were conducted in Hawaii, where the species successfully spawned in captivity.[38] The only barrier in these studies to successful production was problems with commercial food items.[43] An in vitro cell culture has recently been established for the species, which will allow long term management of potential viral diseases that may arise during aquaculture of the fish.[44]

The bluefin trevally is one of the premier gamefish of the Indo-Pacific region, although is often overshadowed by its larger cousin, the giant trevally.[45] The fish makes long powerful runs on light tackle, and is a determined fighter.[46] The species readily accepts both bait and lures, with live fish or squid often used as bait and a variety of lures also used on the species. Lures may include poppers, plugs, spoons, jigs, soft plastic lures and even saltwater flies.[45][46] The species inshore habits make it a popular target for spearfishermen also.[12] In Hawaii the species has bag and size limit restrictions in place to prevent further overexploitation.[41] It is considered to be a good to excellent food fish, however many cases of ciguatera poisoning have been attributed to the bluefin trevally.[17] Laboratory tests have confirmed the presence of the toxin in the species flesh,[47] with fish greater than 50 cm likely to be a carrier.[6] The risk of poisoning has also affected the sales of the fish in the marketplace in recent years.[41] Also of concern is one report of infection by a dracunculoid parasite while preparing the fish for eating. In this case, the parasite invaded the victim’s body by entering an open wound while he was filleting the species, and is believed to be one of the first records for such cross contamination.[48] The bluefin trevally has been successfully kept in large saltwater aquaria, but require large water volumes to adapt well.

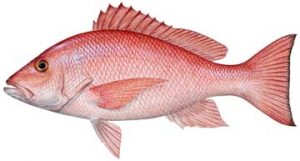

(Poey 1860); LUTJANIDAE FAMILY; also called northern red snapper, pargo colorado, vermelho, pargo del golfo, huachinango del Golfo,

(Poey 1860); LUTJANIDAE FAMILY; also called northern red snapper, pargo colorado, vermelho, pargo del golfo, huachinango del Golfo, Kishinouye, 1920; SCOMBRIDAE FAMILY; also called little tuna, false albacore, spotted tuna, mackerel tuna, skipjack

Kishinouye, 1920; SCOMBRIDAE FAMILY; also called little tuna, false albacore, spotted tuna, mackerel tuna, skipjack

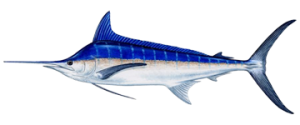

Lacepede, 1802; ISTIOPHORIDAE FAMILY

Lacepede, 1802; ISTIOPHORIDAE FAMILY (Mitchill, 1815); SCOMBRIDAE FAMILY

(Mitchill, 1815); SCOMBRIDAE FAMILY (Cuvier, 1829); SCOMBRIDAE FAMILY; also called kingfish, giant mackerel

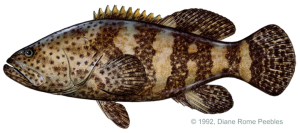

(Cuvier, 1829); SCOMBRIDAE FAMILY; also called kingfish, giant mackerel (Lichtenstein, 1822); SERRANIDAE FAMILY; also called spotted jewfish, southern jewfish, junefish, Florida jewfish, jewfish

(Lichtenstein, 1822); SERRANIDAE FAMILY; also called spotted jewfish, southern jewfish, junefish, Florida jewfish, jewfish